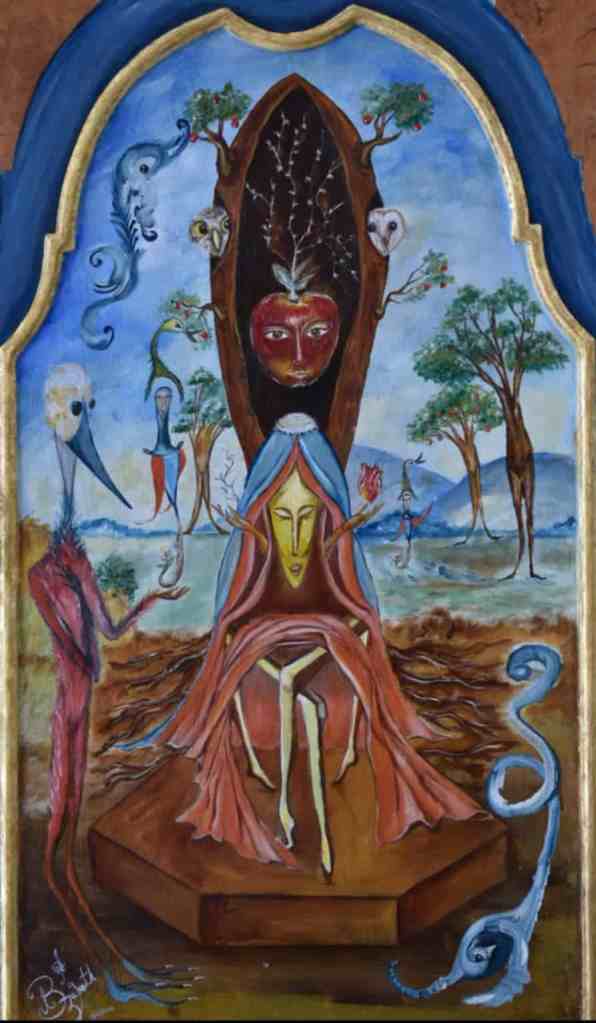

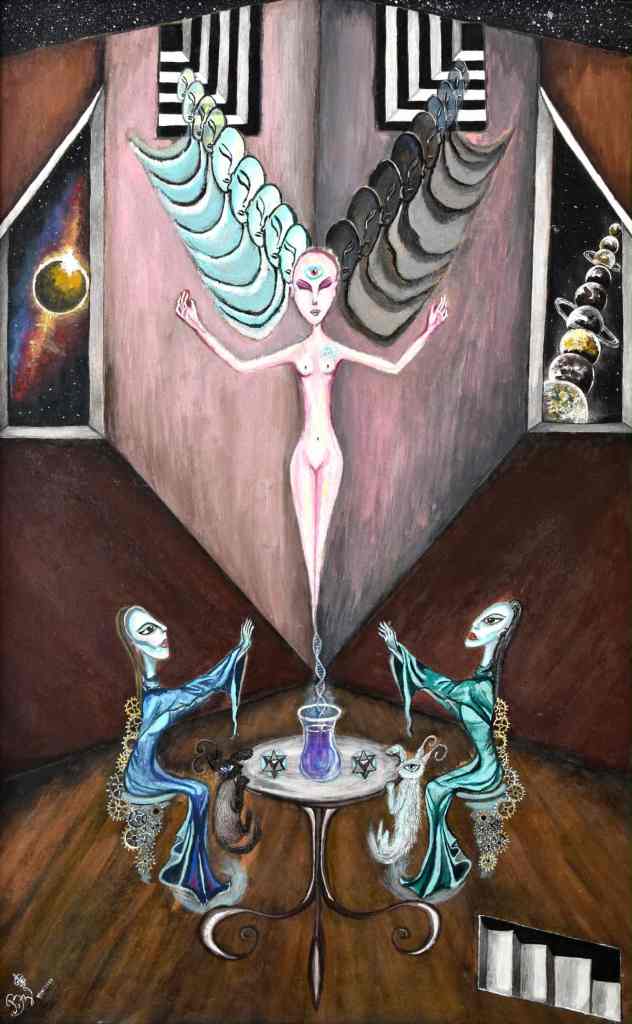

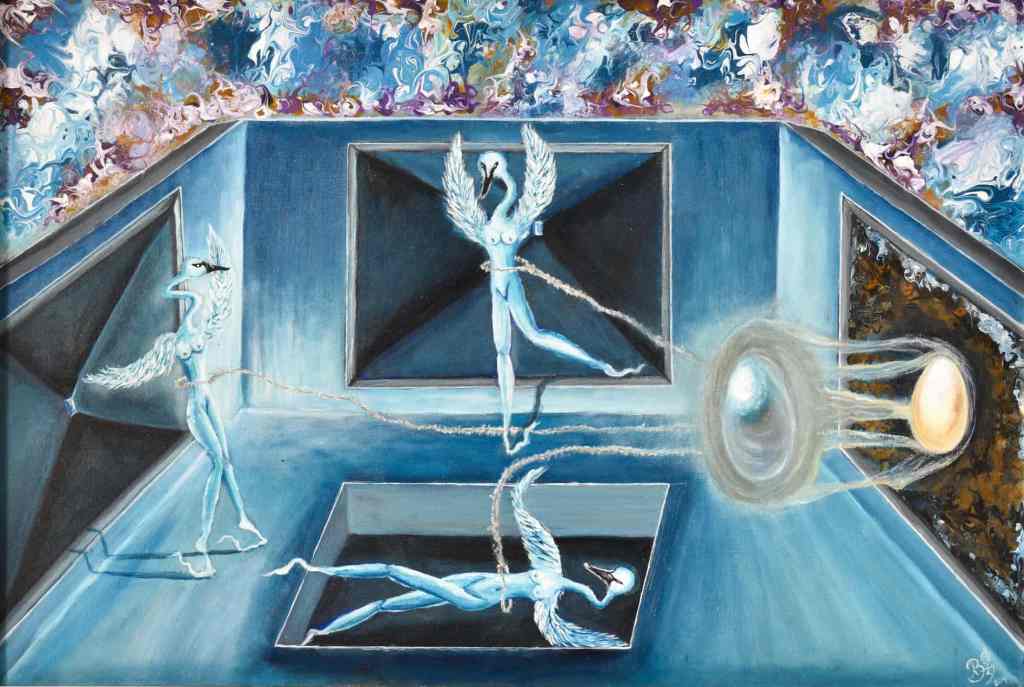

Collage by Mitchell Pluto

The author, Wouter Kusters, has graciously provided his consent for us to share the article he has written. Source from Vol. 36 No. 4 (2025): Filozofija i društvo / Philosophy and Society / SPIRITUALITY AND CONSCIOUSNESS.

Only adjustments to spelling, specifically incorporating American English standards, have been undertaken; no other changes have been made.

Introduction

Psychosis is often regarded as something pathological, as a mental disorder, social disruption or brain disease. And no doubt it is all of those things. If you dig deep enough, you may well find abnormal neurological processes or structures under the brain scanner. In people’s life histories, determining circumstances can also be found (trauma, drug use, stubbornness) that can be linked to later psychosis. Epidemiological research may also show that there is a correlation between the size of the city where one lives and the likelihood of psychosis (Vassos et al. 2012). Such research is relevant insofar as one wants to prevent and cure psychosis. Here, psychosis is regarded as an event, a process or a condition that is causally linked to other events at various biological, psychological and social levels. In order to try to prevent or cure psychosis, one can then intervene at one or more of these levels. Such research is valuable for the purposes of care and self-care, management and self-management. However, explanations, prevention and cures do not automatically lead to understanding. Do you understand how an alcoholic feels by researching the chemical structure of alcohol? Do you understand a painting when you have analysed the quality of the paint or researched the life of the painter? The difference between explaining a phenomenon and understanding a phenomenon is essential to the distinction between the natural sciences and the humanities. In section 2, I show how we can gain a clearer understanding of madness in the humanities using three figures of thought: the bat, the veteran and the visionary. In section 3, I show how we can directly address the question of madness with philosophy, and I will show how and why, in the practice of psychiatry, in addition to the archetype of ‘the doctor’, that of ‘the sage’ – in the guise of the philosopher – is also necessary. In this article I will use the terms psychosis and madness interchangeably , the former more in contexts where a medical, psychological or psychiatric association and discussion is dominant, the latter more when it comes to the psychotic experience itself and the way in which it is connected to areas of meaning that are communal, cultural and philosophical.

Three figures: bats, veterans and visionaries

Bats

In 1974, Thomas Nagel wrote his famous article What Is It Like to Be a Bat? in which he discussed many thorny issues surrounding consciousness, experience and subjectivity. He argued that an organism has consciousness only when ‘there is something that it is like to be that organism’. Consciousness does not exist without subjective experience, and if we do not understand experience, we cannot say that we have explained consciousness. According to Nagel, subjective experience is connected to ‘a single point of view’; a unique position that is fundamentally inaccessible to others. Nagel argues that no matter how hard we try to analyze and describe a particular form of perception (in his example of the bat, echolocation), we will never truly understand what it is like to be a bat. Translated to our case of psychosis, this means that no matter how much knowledge we may have of psychological factors or neurological abnor-malities, something escapes our knowledge: we still do not understand what it is like to be psychotic. However, we can try to imagine and empathise with the experience (see also Dings, 2023). Just as someone without a womb can try to imagine what it is like to give birth to a child. Or just as someone living in the Netherlands can imagine what it is like to live in Gaza. In all these attempts to understand the other, our own frameworks, our own ‘single point of view’, our own perspective, background and way of speaking continue to play a guiding, stimulating but also limiting role. In order to get closer to another person, to understand him or her better, it is desirable to relativise and transcend one’s own perspective, to break through one’s own role, to suspend one’s own initial judgement – and to multiply ‘single points of view’. When promoting understanding of bats, this can be achieved by allowing and investigating stories about bats that are different from the usual ones. The researcher leaves the anatomical laboratory and immerses him-self in the ecology of bat colonies, their interactions with other life forms, and their way of life, foraging, communication and reproduction. In addition, the bat researcher can also go to the library or listen to folk tales about bats. The question then is: how do mythical animal stories, fairy tales, fables and their modern cinematic variants (Batman!) influence our views and interactions with bats? In the case of psychosis research, this would mean avoiding endless, monomaniacal observations, categorizations, data analyses, and generalizing theories based on a single point of view. Instead, one would argue for a shift towards the multifaceted and unruly practice, where real, living, insane people walk around, and by doing participatory fieldwork there, to gain a better understanding of the ecology of madness, language, and expressions in art and culture (think also of Van Dongen 1994; Bock 2002). In the library, researchers or other interested parties can also find masses of literature, outside the psychiatric discourse, that undermines the assumptions of the medical view. Questions such as those posed by Thomas Nagel concerning the basis of experience, language, and life, have been asked by many philosophers and other thinkers with regard to madness. And stories in which suggestions for answers are given are part of the canon of literary and non-literary fiction and non-fiction. (See Ramirez et al. 2024). A value such as ‘respect for (neuro)diversity’ is indispensable in this context of the pluralistic search for understanding of madness and other variations in experience. In order for single points of view to interact productively with each other, and possibly merge, and to arrive at a story about – or if not, perhaps a glimpse of it – the foundation, the core or the essence of the bat, a leap of imagination is needed, a receptivity to the radically different, a shift in language from identifying description to expression and groundless metaphor. Since everyone’s single point of view ultimately remains essentially unattainable, it is more a matter of a plurality of stories circling around single points of view than of striving for proven but meaningless evidence and generalizations. Which interpretation, which story sounds best, which one is most plausible in which context? Who makes themselves heard, at what pitch, and from what point of view? Nevertheless, the fact remains that at the end of the day, it is only the bat that is a bat, an anomaly in the ho-mogeneous darkness, and it continues its night flight.

Veterans

Now I turn to the second analogy, that of veterans. From the considerations of Nagel and other philosophers who deal with experience, consciousness, in-terpretation and subjectivity, we can learn about what it means to ‘understand something/someone’, and about our relationship with psychosis, with madness, with the other. Nagel’s bats themselves, however, are not particularly concerned about this. They do not talk back to biologists and ecologists. Outside of fables, they do not transform themselves into humans. Those who do talk back are war veterans, war refugees and other people who – willingly or unwillingly – are experts in the field of war. Here I will discuss the case of veterans, since there are such inspiring analogies between this group and people with psychosis. To understand what war is, it might suffice to study history books that explain why wars break out, how the fighting proceeds, and how they end. You could learn lessons about international relations, about how war can be prevented, and how it can be waged. But would you then understand what war really is? For that, you need the stories and eyewitness accounts from those who have experienced it themselves. But why would you want to hear these stories in the first place? Is it curiosity or a thirst for sensation? Sometimes it is similar to the kind of interest that exists for madness, namely, out of a thirst for sen-sation, but often it is more than that.Let us consider war as an analogy for psychosis, and traumatised soldiers and war refugees as people who have experienced psychosis. People listen to the stories of veterans, refugees and people with psychosis in order to care for them and help them. And a great deal of research has already been done on people who have been traumatised by war. As a result, terms such as shell shock, trauma and PTSD have been around for a long time (see Bistoen, 2024). Trauma therapy can be used to treat refugees and (former) soldiers with PTSD, and in a similar way, (former) psychotic patients receive therapies in which they learn to recover further. These are desirable therapies for the management and (self-)management of people with problems. However, in recent years, people have taken a different view of such individual-focused trauma therapy. According to many trauma theories, trauma – and, analogously, psychosis – is an individual, psychological and/or biomedical problem. However, many of those who have escaped war are struggling with feelings and memories that have social, moral and existential implications. They have been ‘affected’ by the war and changed by it, but not necessarily only because they are victims or personally traumatized. Their problem is not a disturbance of their own psychological balance, but concerns the war itself – just as madness is often not about the ‘experience of it’ or the psychological disturbances it causes, but about the madness itself. Anthropologist Tine Molendijk (2021) and social scientist Hend Eltanamly (2024) show that many of the problems experienced by (former) military personnel and refugees revolve around guilt and shame, and that they are not only victims, but can also be perpetrators, bystanders or witnesses. I will describe the case of refugees in the same way as that of veterans, which is not to imply that there are no significant differences between these two groups, but I will refrain from discussing this in this article. War experiences prove to be complex, just like war itself; some long to return to it, while others ‘see’ – and experience war behind the façades of a peaceful society. In her research into moral injury among returning military personnel, Molendijk discusses issues such as moral disorientation, value conflicts, moral detachment, and ethical struggles. She demonstrates that the dynamics between experiences, memories, thoughts, and feelings are not merely an individual process, but are embedded in the way these issues are discussed and perceived in their immediate environment, as well as in the media and society. As with the bat, archetypal images, myths, and stories also play a role in the background. For (self-) control and (self-)restraint, the individual perspective on war trauma is sufficient in some cases. But in order to relate to good and evil, to war and peace as a society, it is important to gain a better understanding of what war is, and it is not just about getting the traumatized back on track to normality. Similar lessons apply to psychosis. To know what psychosis really is, observational research into individual experiences and individual behavior is insufficient. In some cases, my metaphor of war for madness coincides with the madness of war: war trauma can manifest itself as psychosis. Think, for example, of high-profile cases such as that of terrorist schizophrenic Andreas Breivik, the Unabomber, or some of those who joined IS, but also of all those who fled war zones and later became ‘psychotic’. Just like war trauma, psycho-ses are about something, which can be paraphrased as a different world, or a different kind of reality, and only by connecting with the underlying deep-er motives can we learn something that is useful to us beyond (self) manage-ment. Finally, with regard to the war comparison: we can take this even fur-ther, as madness often involves conflict or struggle, although this may refer less obviously to a ‘real’, observable struggle such as that in war. In philosophy, philosophical anthropology and psychology, there is a long history, a library full of theories, views of humanity and the world, according to which life and the soul are fundamentally characterised by struggle, conflict and contradictions. Heraclitus should be mentioned as the first philosopher in this regard, and from there we can follow a family of thinkers, from Hobbes to Nietzsche, Hegel, Deleuze and Haraway, but also Freud and Lacan. In ideas and theories about madness that refer to these thinkers, there is often a tacit assumption that the primary fundamental state is one of chaos, madness or war, and that order, normality and peace are only secondary temporary masks of the deeper truth: deviations in the darkness. Be that as it may, when psychosis is reduced to a neurological abnormality or a mental disorder, we miss the opportunity to reflect on such deeper motives, packed in inevitable tensions and paradox-es within subjectivity and reality, on questions of good and evil, on ontologies and alternative complex meanings, which would be a missed opportunity for all those involved in war and madness. For the case of war, this means that we could better speak of “moral injury” instead of PTSD (see e.g. Molendijk 2021). For the case of madness, we could coin a term like “existential inju-ry”. The crux in both cases is that the “injury” is not only located within the psyche, within the individual, but also reveals something about the situation outside the war, outside the psychosis. In the case of war, this means that a certain moral hypocrisy within society is revealed by the returning veterans. In the case of psychosis, this means that a certain ontological uncertainty is revealed that is also present beneath common sense reality (see Feyaerts et al. 2021, and Kusters, 2020).

Visionaries

In addition to a comparison with bats and veterans, I would like to bring the theme into the domain of prophets, visionaries, religious founders and sect leaders. In earlier times, there was more receptivity to what we now characterize as religious language, religious beliefs and religious experiences. Those who reported on their experiences, adventures and developments, their world-view and views on reality, as well as their inner struggles and conflicts, did so against a backdrop in which supernatural, religious or spiritual spheres and concepts were self-evident. For concerns, special thoughts and insights, one could turn to religion and to those who claim to know more about it. This is still possible today, as God’s house has no locks on the door, but the first choice in cases of spiritual distress is often that of the doctor or psychologist in the agnostic medical field, which is permeated by a scientific secular attitude and a single point of view on knowledge. Moreover, when one attempts to understand madness in such a detached ‘expert’ manner, one does so from a worldview in which there is little or no room for religious experiences or spirituality. Nevertheless, people often talk about something like spirituality, both those who were ‘in the madness’ themselves and their loved ones. We could consider this spirituality as part of those possible metaphorical stories revolving around that single point of view (see the bat parallel), or as expressions of experiences and feelings that cannot be reduced to an individualistic trauma approach (see the veteran parallel). However, much of what is classified as spirituality has its own dimension: a language with accompanying practices that can be called religious. As far as madness is concerned, this dimension includes messages from self-proclaimed prophets, visions from alleged visionaries, complex expressions of religious ecstasy from those who have seen the light or received other signs from the other side. Sometimes, however, all this is just accepted as ‘part of a possible metaphorical story’. Then the first acute religious/psychotic experiences, the first ecstasies and raw expressions are somewhat tempered, cast into a narrative form, thereby normalised and thus made communicable. That is to say, a narrative approach may reveal something, but may also hide those aspects of experience that essentially resist narration (see Saville Smith 2023). Incorporation into a narrative can be done by the person making the interpretations – whether that is the ‘mad(wo)man’ herself, a second person addressed, or a third person who observes and analyses the mad state. The un-folding, storage and interpretation of mad language and experience within an appealing larger and protective discourse, such as that of religion, nevertheless seems attractive, and it is understandable that compartmentalization in mental health care has also led to the specialism of spiritual care. But then still, even if the proverbial bat and the stray sheep are welcomed by a spiritual counsellor into the bosom of a religious circle, each specific religious movement also imposes its own standards. There is a long tradition of separating the wheat from the chaff, the ‘good news’ (the ‘evangelism’ – etymologically: eu-angelos, good news) from the bad, namely the devilish whis-perings and temptations of selfishness and evil. In other words, the spiritual counsellor must also distinguish between supposed individual pathology and genuine religiosity (see, for example, the many discursive twists and turns that spiritual counsellors such as Ypma and Arends have to contort themselves into). Questions about authority, the legitimacy of judgements, interpretations of experiences and choices of interpretative frameworks are just as thorny and com-plex problems here as they are in neurobiological or psychological approaches. In addition, in the larger context of society, with its diverse range of care practices, there is also a tendency to promote and sell one’s own discourse, practices, and religion in a market of well-being and happiness, in competition with neurobiological medicines and psychological talk therapies. Results are measured in terms of success, normalisation, healing – and ultimately in terms of financial profit and loss. And so religion and a religious approach to madness can gradually change from an attempt to understand madness into a tool for managing madness. The religious sphere is then changed and transformed, ‘made productive’, into one of the many tools that can be used not so much to understand madness, but to suppress or destroy it (think in this context of empirical quantitative research into ‘the usefulness’ of religion as protection against mental disorders; for an overview study, see e.g. Hoenders and Braam 2020). For pragmatic purposes within our fluid, fast-paced, pro-duction-consumption society, this may make sense, but in order to refine and broaden our understanding of madness, a broader and deeper reflection on and critique of religion itself is needed (compare Saville-Smith’s attempt (2023) to safeguard what he calls ‘acute religious experience’ from both reduction and instrumentalisation by established religions and by established psychopatho-logical frameworks). Finally, a reflection on madness that focuses on the ques-tion of the degree of religiosity in the experience can say little about actual cases of violent religious madness when the social, moral and political context is left out of consideration.

Mad philosophising

So far, I have described philosophical circumlocutions, via the bat, the veteran and the visionary, to show what kinds of philosophical and other considerations play a role in the broad field of psychiatry and philosophy. In a narrower subfield, research questions and philosophical reflections are often reduced to a few key questions, largely driven by the concerns, problems and discussions between psychiatrists and other healthcare providers. An important one is the classic discussion surrounding body-mind issues: should patients be treated for something psychological or something physical? Is a psychiatric disorder something that can be remedied by talking – affecting the psyche, or primarily by medication – affecting the body? Within this narrower type of philosophy of psychiatry, the question of this bio-psycho pair is leading, and the philosophical discussion revolves around that apparent contradiction. Those who speak about psychosis, about madness, are experts in either the bio or psycho approach to human beings, and insofar as there are any ‘real patients’ involved in this debate, they function more as data suppliers or consumers (with questions such as: ‘Was what you experienced something with which talking helped, or did you mainly benefit from medication?’) who function more as numbers in statistics than as experts intimately informed about madness. In this kind of philosophy of psychiatry – in the narrower sense – the problematic position in the workplace is in fact repeated: the observer, the psychiatrist or psychologist, has knowledge of statistically substantiated generalizations, reflects on them, and the patient has a problem that needs to be managed and solved with the cheapest possible tools. Therefore, much of this philosophy of psychiatry ultimately revolves around the question of what the most efficient (self-) management methods are, whereby understanding what is being managed away is considered irrelevant. In the paragraph above, I argue that the language and experience of madness itself already escapes the framework of psychopathology, and that it boundlessly follows its nocturnal flight, its deviation in the dark, through domains that are fundamentally terra incognita, proverbial war zones, where in harmonious times of peace and harmony one would rather not set foot, and where one prefers to keep everything controllable and manageable from a distance. Better no people there! But robots, drones and ‘fighting machines’! Better to combat the disturbed, non-functional functioning of the amygdala or hippocampus with a laboratory-tested drug than to wrestle with the angel like Biblical Jacob. In the following paragraphs, I will show some of these struggles, without neutralising them through the distant, controlled – and controlling – language of psychiatry. In the rest of this article, drawing on the more extensive and refined understanding of madness that we have gained from the three figures of thought, I will focus solely on these two, on the two ‘single views’ of philosophy and madness, on their mutual relationship, their contradictions, their similarities, and the ways in which they can together give rise to meaningful and meaningless new languages and practices.

Perplexity and hyperreflection

What philosophical movements and perspectives – what single points of view – can we discern in madness? Let us explore this by assuming that the mad person may not always write fully developed philosophical research papers, but that he or she is a kind of proto-, crypto- or para-philosopher (see Feyaerts et al. 2021). What structures and themes do we find? We find access to the do-main where madness is the principle of philosophy through the terms ‘perplexity’ and ‘hyperreflection’ from psychiatry. The most widely used handbook in psychiatry, the DSM, lists ‘confusion or perplexity’ as a characteristic of the peak of a psychotic episode. Anton Boisen, a theologian who was personally acquainted with madness, noted (1942: 24):

The madman feels absorbed into an eerie and mysterious realm. The generally accepted principles of judgement and reasoning have disappeared. He no longer knows what to believe. His condition is one of utter perplexity regarding the essential foundations of his existence. Questions such as ‘Who am I?’, ‘What is my role in life?’ and ‘What is the universe in which I live?’ become matters of life and death.

Such testimonies of insane confusion and perplexity are legion. The term ‘hyperreflection’ also comes from (phenomenological) psychiatry. Instead of the insane person thinking too little or incorrectly, this refers to the overwhelming intensity and speed of self-conscious thinking in psychosis. Louis Sass states (2003: 155): ‘Hyperreflexivity refers to a kind of exaggerated self-awareness, a tendency towards objectifying attention that focuses on processes and phenomena that one normally experiences as part of oneself. Edward Podvoll (1990: 190) says: “Everything in the mind multiplies: forming clones, branching out into endless varieties of itself, without ever tiring, producing a jungle of new types of thoughts, an insatiable evolution that fills the whole world.” In psychiatry, such a combination of perplexity and hyperreflection is usually considered a ‘disturbed’ experience (note commonly used terms such as ‘exaggerated’ and ‘excessive’ in the definitions), because it often hinders functioning in everyday practice (see, for example, Fuchs, 2020). Hyperreflectivity is often considered and described as ‘delayed consciousness’, as the connection with the environment seems to be slower and more difficult. The experience itself, on the other hand, is often perceived as ‘accelerated’ – an acceleration that caus-es one to leave the slower rhythms of everyday life behind and lose contact.In a philosophical mode, we can relate perplexity and hyperreflection to the basis of philosophy, namely, wonder and reflection. Madness as a combi-nation of perplexity and hyperreflection can then be considered ‘paraphilosophy’, ‘protophilosophy’, or perhaps ‘hyper-philosophy’, driven by the same – but more intense – impulses as ordinary philosophy (see also Derix 2024). When we analyse the expressions of madness more closely, we can distinguish three (linguistic) types of expression in which such proto-philosophy of mad-ness is reflected. First of all, there is the domain of natural language. This is available to everyone, and the madman uses it to articulate his experiences, to say what is going on. Personal backgrounds resonate here, but in general, the means of everyday language are used to try with all one’s might to express something unusual. Consider the enigmatic remarks of the German schizophrenic writ-er Harald Kaas:

When madness rises like water and passes the high-water mark, there are moments when something is revealed that you cannot speak about openly. That is why it is most clearly announced in the stammering of those who have been burned by its light and who are condemned to remain silent about it for the rest of their lives. (Kaas 1979: 61)

In madness, ordinary language explodes and turns into an infinite game of transformations and reflections of signifiers and signifieds, in which the metaphorical character is striking. Some metaphors stand out, such as those of light and dark, fullness and emptiness, and that of fluid and fire. A second domain of expression is the language of mysticism, religion and spirituality – already discussed above in the context of the visionary. It should come as no surprise that extraordinary experiences are described using language from a domain that deals with extraordinary phenomena, questions and problems concerning life and death, good and evil. Terms such as ‘revelation’, ‘enlightenment’, ‘rebirth’ and ‘apocalypse’ are therefore common in delusional discourse. It should be noted here that the avoidance of religious language in most psychiatric practices has not resulted in a more meaningful discourse for developing viable, meaningful narratives from the mad proto-philosophy. Outside of the practices of psychiatry, however, academic medical anthropology has managed to record meaningful narratives (see, for example, Pandolfo 2018 and Van Dongen 1994). In practice, however, the mad(wo)man with their meaningful experiences often ends up out of the frying pan into the fire of med-ical disease discourse, with or without a quasi-spiritual sauce. Charles Taylor (2007: 809) makes a sharp observation on this subject: “The discarding of re-ligion was intended to liberate us, to give us our full dignity as acting persons by shaking off the tutelage of religion, and thus of the church, and thus of the clergy. But now we are forced to turn to new experts, to therapists and doctors who exercise the kind of control appropriate to blind and compulsive mecha-nisms and who may even administer drugs to us. Our sick selves are addressed even more condescendingly than the believers of yesteryear in the churches; they are treated merely as objects.” However, as I described earlier, this does not imply that the specialised branch of mental health care known as spiritual care could always provide an appropriate place for the insane.A third expression of proto-philosophy is… philosophy itself. There is no lan-guage or philosophical approach capable of adequately expressing the domain of madness, since it is a domain where language, experience and reflection are (still and again) inseparable, where receptivity to the world is on the same level of experience as the interpretation and creation of the world (see also the dis-cussion at the end of 2.2). But when madness does speak, the most obvious types of philosophy are those that revolve around such complexities and are closely related to the issues and themes of mysticism, spirituality and religion. These are philosophies that are closely linked to the moment of wonder (and perplex-ity) and are not yet too deeply entangled in their own discourse or tradition. When we consider the floating cosmologies, the comprehensive systems and textual reveries that developed further from mad proto-philosophy, we see some common features. First of all, there is a tendency towards monism. The path to madness is characterized by boundary-crossing thinking; a tendency burned by its light and who are condemned to remain silent about it for the rest of their lives. (Kaas 1979: 61) In madness, ordinary language explodes and turns into an infinite game of transformations and reflections of signifiers and signifieds, in which the metaphorical character is striking. Some metaphors stand out, such as those of light and dark, fullness and emptiness, and that of fluid and fire. A second domain of expression is the language of mysticism, religion and spirituality – already discussed above in the context of the visionary. It should come as no surprise that extraordinary experiences are described using language from a domain that deals with extraordinary phenomena, questions and problems concerning life and death, good and evil. Terms such as ‘revelation’, ‘enlightenment’, ‘rebirth’ and ‘apocalypse’ are therefore common in delusion-al discourse. It should be noted here that the avoidance of religious language in most psychiatric practices has not resulted in a more meaningful discourse for developing viable, meaningful narratives from the mad proto-philosophy. Outside of the practices of psychiatry, however, academic medical anthropology has managed to record meaningful narratives (see, for example, Pandolfo 2018 and Van Dongen 1994). In practice, however, the mad (wo)man with their meaningful experiences often ends up out of the frying pan into the fire of medical disease discourse, with or without a quasi-spiritual sauce. Charles Taylor (2007: 809) makes a sharp observation on this subject: “The discarding of religion was intended to liberate us, to give us our full dignity as acting persons by shaking off the tutelage of religion, and thus of the church, and thus of the clergy. But now we are forced to turn to new experts, to therapists and doctors who exercise the kind of control appropriate to blind and compulsive mechanisms and who may even administer drugs to us. Our sick selves are addressed even more condescendingly than the believers of yesteryear in the churches; they are treated merely as objects.” However, as I described earlier, this does not imply that the specialized branch of mental health care known as spiritual care could always provide an appropriate place for the insane. A third expression of proto-philosophy is… philosophy itself. There is no language or philosophical approach capable of adequately expressing the domain of madness, since it is a domain where language, experience and reflection are (still and again) inseparable, where receptivity to the world is on the same level of experience as the interpretation and creation of the world (see also the discussion at the end of 2.2). But when madness does speak, the most obvious types of philosophy are those that revolve around such complexities and are closely related to the issues and themes of mysticism, spirituality and religion. These are philosophies that are closely linked to the moment of wonder (and perplex-ity) and are not yet too deeply entangled in their own discourse or tradition. When we consider the floating cosmologies, the comprehensive systems and textual reveries that developed further from mad proto-philosophy, we see some common features. First of all, there is a tendency towards monism. The path to madness is characterized by boundary-crossing thinking; a tendency the opposition between philosophy and madness, not to wash away, with the removal of the traditional philosophical bathwater, that child called madness, which is like a deviation in the darkness of chaos.

In conclusion

The thrust of this article is that more understanding and more philosophy are needed when thinking about madness, and I hope to have offered some ideas, perspectives and possibilities in this article. I first sought greater refinement and understanding with three figures of thought, and then took the bull of philosophy directly by the horns. In doing so, I was critical of the limiting and one-sided discourse of psychiatry, as well as that of a philosophically inspired form of psychiatry, in which philosophy is used only instrumentally: as a means to improve psychiatry and better manage the patient’s health, rather than as a domain of fundamental questions and transdisciplinary reflections. This does not mean that the questions of the philosophy of psychiatry in the narrower sense are nonsensical; on the contrary, they are essential to the ins and outs of mental health care practice and must be heard and spoken aloud. However, when we talk about a philosophy of psychiatry in a broader sense, it is not self-evident who has the first word and who has the last, nor who should be heard first and who last. In this respect, there is an underground struggle or conflict between the archetypes of the sage, the doctor, and the madman. It is up to us — to para- and hyper-philosophers, but also to those who feel no need for prefixes to the title of philosopher — to transform such a struggle into a verbal and non-verbal interplay which, although ‘nothing remains’, ul-timately gives Jacob’s struggle with the angel the appearance of a dance, as a livable deviation in the darkness.

References

Arends, Cor. 2014. If Billy Sunday Comes to Town—Delusion as a Religious Experience: The Biography of Anton T. Boisen from the Perspective of Foundational Theology. Zurich/Berlin: LIT Verlag.Bistoen, Gregory. 2024. “Traumaherstel zonder methodisch houvast.” In: Kusters, Wouter, ed. Trauma en waarheid. Leusden: ISVW Uitgeverij: pp.: 99–118.Bock, Thomas. 2002. Psychosen zonder psychiatrie. [Dutch translation of Lichtjahre, Psychosen ohne Psychiatrie, 2001, Psychiatrie Verlag, by M. Stoltenkamp]. Utrecht: Candide.Boisen, Anton T. 1942. The Form and Content of Schizophrenic Thinking, Psychiatry5: 23– 33.Derix, Govert. 2024. Hyperfilosofie. Op zoek naar wijsheid in onwijze tijden. Utrecht: Magonia.Dings, Roy. 2023. Experiential knowledge: From philosophical debate to health care practice? Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 29 (7): 1119–1126.Dongen, Els van. 1994. Zwervers, knutselaars, strategen. Gesprekken met psychotische mensen.University of Utrecht: Dissertation.

SPIRITuALITY AND CONSCIOuSNESS │ 863Eltanamly, Hend. 2024. “Oorlog, vlucht en ouderschap.” In: Kusters, Wouter, ed. Trauma en waarheid. Als taal tekortschiet. Leusden: ISVW Uitgevers: pp.: 33–50.Feyaerts, Jasper, Wouter Kusters, Zeno Van Duppen, Stijn Vanheule, Inez Myin-Germeys, and Louis Sass. 2021. Uncovering the realities of delusional experience in schizophrenia: a qualitative phenomenological study in Belgium. Lancet Psychiatry 8(9):784–796.Fuchs, Thomas. 2020. “Psychopathologie der Hyperreflexivität.” In: Randzonen der Erfahrung. Beiträge zut phänomenologischen Psychopathologie. Freiburg: Karl Alber Verlag: pp.: 21-43.Hoenders, Rogier, and Arjan Braam. 2020. The role of spirituality in psychiatry: important but still unclear. Tijdschrift voor psychiatrie62: 955–959.Jaspers, Karl. 1955. Schelling. München: Piper Verlag.Kaas, Harald. 1979. Uhren und Meere: Erzählungen. Munich: Hanser Verlag.Kusters, Wouter. 2020 [2014]. A Philosophy of Madness. The Experience of Psychotic Thinking. [translated from the Dutch Filosofie van de waanzin. Fundamentele en grensoverschrijdende inzichten. Rotterdam: Lemniscaat.] Cambridge (MA): MIT Press. Molendijk, Tine. 2021. Moral Injury and Soldiers in Conflict. Political Practices and Public Perceptions. London: Routledge.__. 2024. “Oorlog als ontdekking van de waarheid.” In: Kusters, Wouter, ed. Trauma en waarheid. Als taal tekortschiet. Leusden: ISVW Uitgevers: pp.: 17–32Nagel, Thomas. 1974. What Is It Like to Be a Bat? The Philosophical Review 83 (4): 435–450.Pandolfo, Stefania. 2018. Knot of the Soul. Madness, Psychoanalysis, Islam. Chicago: Chicago University Press.Podvoll, Edward. 1990. The Seduction of Madness: Revolutionary Insights into the World of Psychosis and a Compassionate Approach to Recovery at Home. New York: HarperCollins.Ramírez-Bermúdez, Jesús, Ximena González-Grandón,, and Rosa Aurora Chávez. 2024. Clinical narrative and the painful side of conscious experience. Philosophical Psychology 38 (1): 353–377.Sass, Louis A. 2003. ‘Negative Symptoms’, Schizophrenia, and the Self, International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy 3(2): 153–180.Saville-Smith, Richard. 2023. Acute religious experiences. Madness, psychosis and religious studies. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.Schelling, Friedrich W. J. 2006 [1815]. The Ages of the World. [Translated by Jason M. Wirth from the original Die Weltalter]. New York: State University of New York Press. Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Vassos, Evangelos, Carsten B Pedersen, Robin M Murray, David A Collier, and Cathryn M Lewis. 2012. Meta-Analysis of the Association of Urbanicity with Schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 38 (6): 1118–1123. Ypma, Sytze. 2001. Tussen God en gekte. Een studie over zekerheid en symbolisering in psychose en geloven. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen: Dissertation.

Wouter Kusters is a Dutch philosopher and linguist. He is the author of Filosofie van de waanzin which was awarded with the Socrates Award in 2015 for the best philosophy book in Dutch. In 2005 he published a smaller essay “Pure waanzin” (Pure Madness) in Dutch, that also won the Socrates Award. A Philosophy of Madness has been published in English in December 2020 at MIT Press.