African art has been a part of my childhood. My mother, Nadya Levi, was a sculptor who collected African art, and my father, Herman Norden, was an antique dealer who had a room in his house filled with African art, books, and stuffed birds. As a child, I went to London many times with my mother for auctions, where we met interesting people like Patricia Withofs and Gaston de Havenon. I also remember Mrs. Huguette van Geluwe in Brussels, where we went to seek her opinion on Congolese pieces, or Willy Mestach. And there were Simpson, Charles Raton, and Baron Rollin, who would visit us in Antwerp, and as a little boy, I had to serve coffee and help clean the display cases.

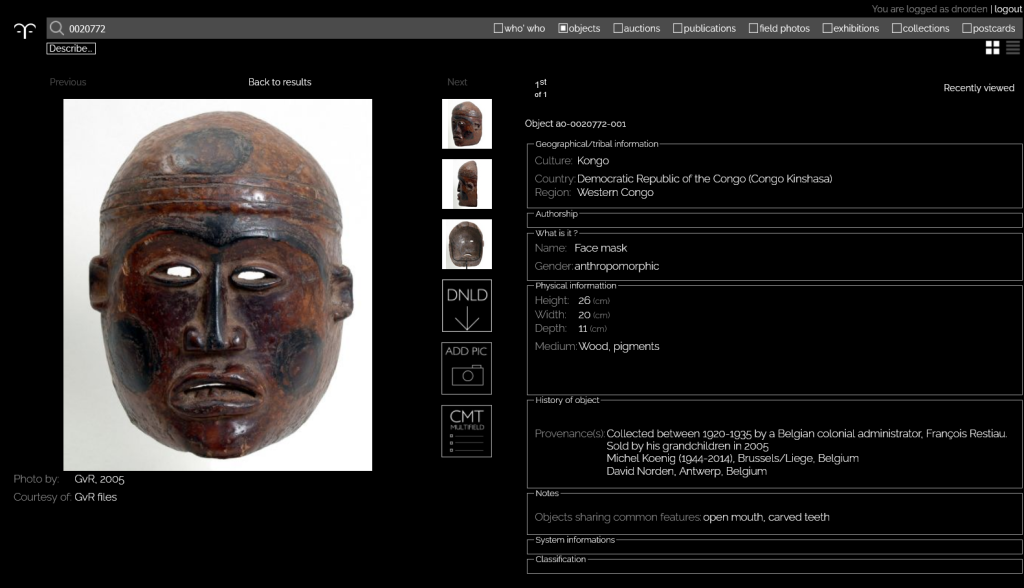

My mother’s collection of Bassa and Dan masks, all hung side by side, many of which were acquired from Paolo Morigi. My first purchase was a small miniature Etruscan stone tablet depicting a lion.

I am always looking for an object that evokes emotions in me. I would love to acquire a beautiful object that belonged to Henry Pareyn, the first collector dealer in Antwerp around 1910. I have always derived more pleasure from acquiring objects than from selling them, but I am not a fetishist who cannot part with them.

What determines the value of the works? The value of an object often depends on the buyer. I could say that it is the beauty and antiquity associated with the provenance, but in reality, it is the emotion that an object evokes in you that is important, and sometimes the place your imagination gives it.

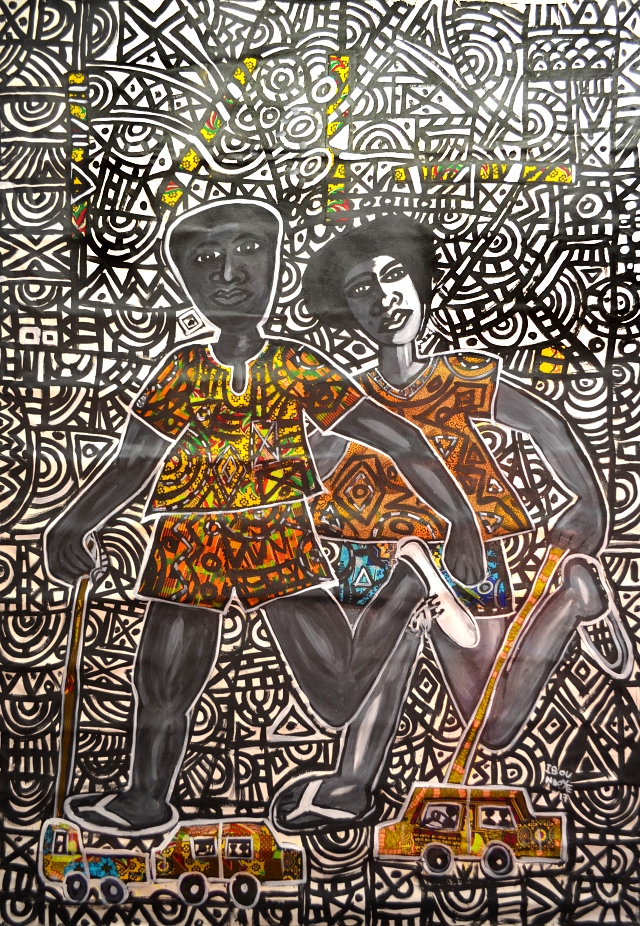

There are so many personalities in this field who have inspired me that I can’t name them all, but first and foremost, it is people with a deep passion and those who recognize the beauty and importance of African art for humanity that inspire me the most. African art has had a tremendous impact and great influence on Western art after World War I, and it is only natural to recognize the importance of this art and its artists.

The African art market represents only 0.8% of the overall antique market.

It is flooded with fakes, and verifying authenticity is reserved for a very small experienced elite with a network of knowledgeable friends. Determining the value is equally unpredictable due to the market’s volatility, as it is too small. However, this provides many opportunities for knowledgeable buyers to make good purchases. The price of African art has declined in recent years for mid-range pieces due to the disappearance of wealthy collectors and the abundance of supply in the market. Only exceptional objects still command high prices.

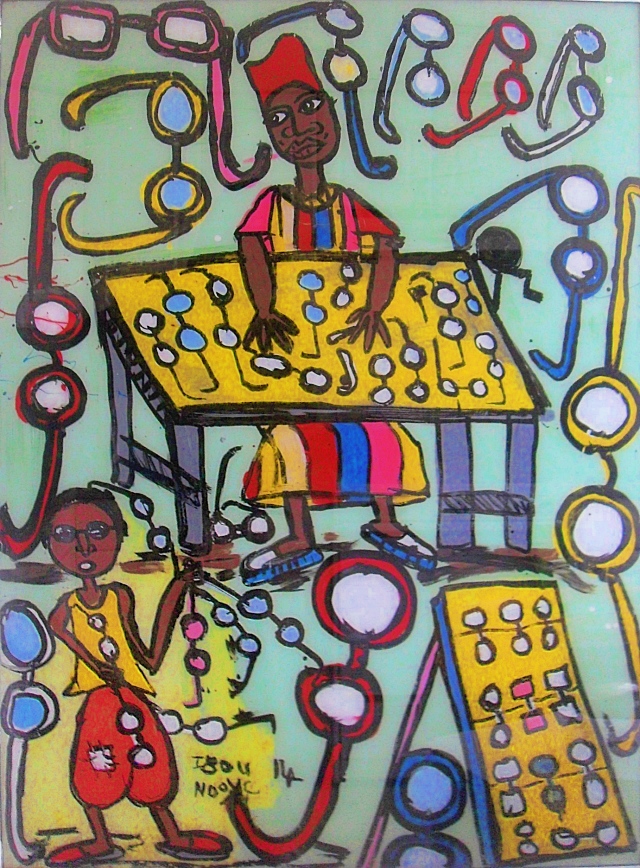

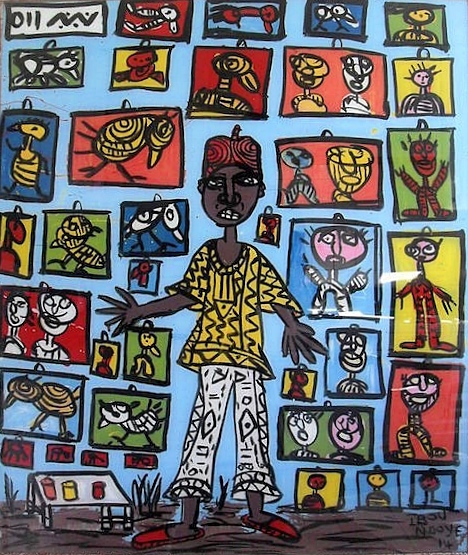

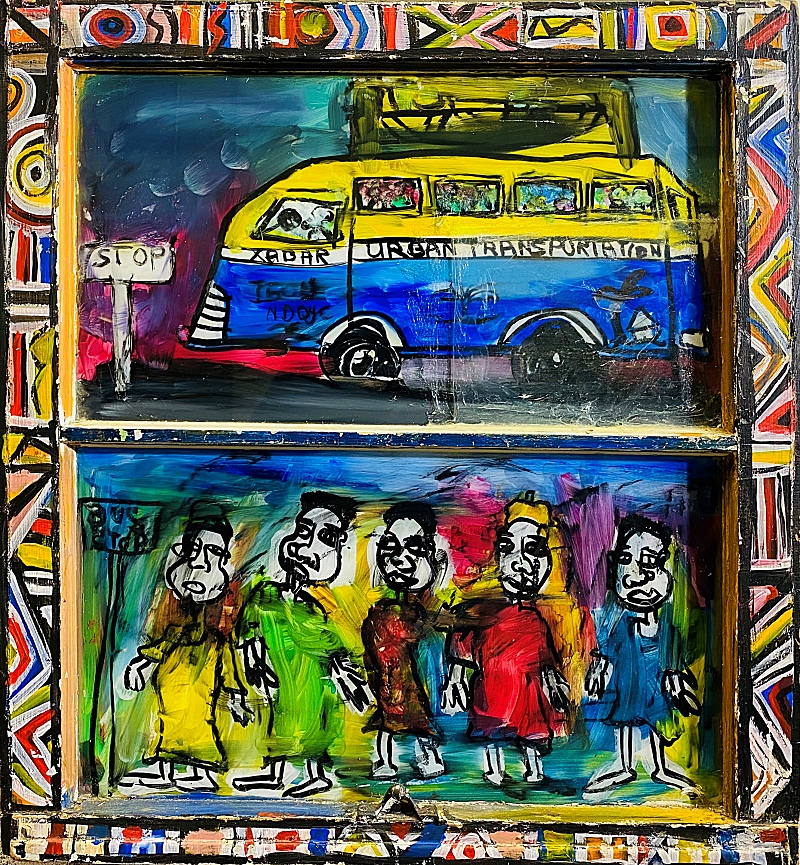

I do see many small collectors entering the market, but they rarely “invest” more than a few thousand euros. The recognition of contemporary African art over the past decade is very encouraging, as it could attract new audiences to African primitive art as well. The role of museums and cultural institutions is crucial in recognizing these cultures. In this regard, the Musée du quai Branly is doing excellent work by offering beautiful exhibitions that attract new audiences. However, the recent demands for repatriation create some discomfort in the market in the short term. But with the recognition of the importance of their own art, in the long term, it should allow an African market to develop in Africa. I also look forward to the creation of museums on the African continent, especially with the opening of the Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar.

Throughout his journey, Norden has found inspiration in numerous figures within the primitive art field. He admires those who possess a deep passion for African art and recognize its significance in the broader context of humanity. The profound impact of African art on Western artistic movements following World War I further fuels his admiration for the art form and its artists. Looking ahead, Norden’s enthusiasm for primitive art shows no signs of waning. With an ongoing book project awaiting completion, he is dedicated to sharing his extensive knowledge and experiences with a wider audience.

Norden places great importance on the role of museums and cultural institutions in recognizing and promoting the significance of African art and its associated cultures. He commends the Musée du quai Branly for its remarkable exhibitions, which attract new audiences and foster appreciation for African primitive art. Norden also expresses anticipation for the emergence of museums on the African continent, with the Museum of Black Civilizations in Dakar serving as a beacon of hope.

David Norden’s lifelong dedication to primitive art has solidified his position as a respected figure in the field. His unwavering passion, discerning eye, and commitment to preserving the legacy of African art continue to shape his remarkable journey. As he eagerly shares his knowledge and explores new horizons, Norden’s contributions play an invaluable role in promoting the beauty and significance of primitive art to a global audience.

Sint Katelijnevest 27/B2000 Antwerpen/Belgium+32 3 227.35.40/david.norden@telenet.be

website where people can browse for available pieces in the shop https://buyafricanantiques.com/

or subscribe to my free newsletter